What Materials Did Leonardo Da Vinci Use to Create His Art?

The Canvas Support

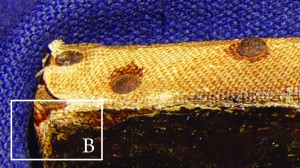

The main characteristics of the linen canvas used for the before version portrait were straightforward: plain tabby weaves with an average thread count of 18 threads per cm warp, and 16 threads per cm weft, crossing each other of class, and with some variations in thickness. The consequence is a warp that is slightly tighter than the weft. That Leonardo would choose available sail instead of a forest console upon which to paint a portrait is really not that surprising. One of the major criticisms put forrad against the Leonardo attribution of the 'Before Mona Lisa' to Leonardo relates to the stance that he would not take used a canvas support. However, when the thing is examined in detail, such stance is shown to be of little importance, as confirmed by Lorusso and Natali in their peer reviewed paper.

The back up, which has a tight warp and a loose weft, is fabricated of linen fabric. The fibroid and irregular weave are indicative of a hand-woven canvas.

Drape study for a Seated Figure. Oil on canvas, c. 1475-1480, Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo had Worked on Canvas

Leonardo executed a number of works on canvass while working under Verrocchio in the 1470s. It is no coincidence that the drapery studies that Leonardo painted on canvass roughly 30 years before, and that are now in the Louvre, display about identical characteristics to those of the before version. Every bit with the 'Earlier Mona Lisa', these canvasses of course were too naturally hand-woven.

The authors of the swell volume, Mona Lisa – Inside the Painting have admitted in the volume that some quotations and analyses from Leonardo's Treatise business organization painting on canvas. In a way, this is an oblique though fair acknowledgement that Leonardo would take had substantial experience with that material, and confirms that not only did he utilize sheet extensively, just executed pregnant works on it. To be even-handed, it is also reasonable to assume that, given the correct preparations, any of his formulas for painting on sail could be configured, perhaps in different combinations, to be equally effective on wood.

The comment in the publication too highlights an issue that until now has rarely been tackled: a comprehensive report of Leonardo's work on canvas. Elisabeth Martin, Naoko Sonoda, and Alain Duval comment: "All the major studies and manufactures on the preparation and pigment compounds of paintings of the Renaissance period in Italia, and specially around Leonardo'southward years, relate to paintings on wood simply, and till recently little or nothing was studied on Leonardo'southward works on canvas or other surfaces." Certainly later the intense examinations undertaken on the 'Before Mona Lisa', i could gain a new understanding of Leonardo's working techniques. Interestingly with this painting, there are really no surprises: it fits with Leonardo'south own detailed and comprehensive directions, as he outlined both in the voluminous writings and reports assembled throughout his life, only also specifically in his Treatise On Painting, required reading for any truthful artist and student of Renaissance painting. No other creative person of his time left such a wealth of information, either virtually his particular vocation, or useful instructions on how to achieve top results.

Historical Context

The turn of the 16th Century marked a significant period of transition in the use of artists' materials. Knowledge about the use of new media from advanced Flemish and Venetian masters was condign more widespread. Oil and artificial pigments were starting to become popular: in fact Leonardo was using oil as a binder and medium as far back every bit his fourth dimension as a student of Verrocchio. Upward to the 16th Century, wood was the almost popular support for painting, and prior to 1470 almost nothing of importance in Western art was painted on canvas. Leonardo'due south 'Lady with the Ermine' and 'La Belle Ferronniere' were painted on walnut panels. The Louvre 'Mona Lisa' on the other paw, was painted on poplar, a wood more often establish in Lombardy than Tuscany.

Canvass was, by 1500, already in use by painters in Italian republic. Information technology is known that c.1499-1500 Leonardo visited Venice via Mantua, on his render to Florence later his sojourn in Milan. In Mantua, he would likely have met with Andrea Mantegna, the Court Painter for Isabella d'Este at that time. Mantegna was a bully exponent of painting on canvas, and might well take influenced Leonardo. Vittore Carpaccio, from Venice, is also of particular relevance, as he was of the same age and lived during the same times every bit Leonardo as did Giorgione. It is considered that Leonardo collected some new ideas from Venetian masters, certainly virtually the apply of glass in pigments, in addition to the use of canvas equally a support. All of this occurred just before he ready to task on Mona Lisa.

It tin can clearly be seen that from and subsequent to Leonardo'south working life, the use of canvas as a back up was coming into greater use: not simply with Dutch and Venetian masters, simply too with Germans, Florentines and other Italians. There is also well documented evidence of masterworks by Leonardo's contemporaries some of whom, equally stated above, he would accept been in straight contact, including:

• Sandro Boticelli (1446-1510)

'The Birth of Venus', c.1482-1485 (Florence) 'Mystic Nativity', c.1500 (London)

• Giorgione (1477-1510)

'The Tempest' c.1508 (Venice)

• Andrea Mantegna (c.1431-1506)

'The Holy Family with St. Elizabeth and the Immature St. John', c.1498-1499 (Dresden)

'The Mourning over the Expressionless Christ', c.1501 (Milan)

• Raffaello Santi (Raphael) (1483-1520)

'Lady with a Unicorn', c.1504-1505 (sail, transferred to panel)(Rome)

'The Sistine Madonna', c.1516 (Dresden)

'Portrait of Count Castiglione', 1515 (Paris)

• Tiziano Vecellio (Titian) (1488-1576)

'La Bella', 1536-1538 (Florence)

'Ecce Human', 1543 (Vienna)

'Portrait of the Creative person', c.1565 (Madrid)

• Vittore Carpaccio (c.1455-1525)

'St. Ursula'southward Arrival in Cologne', 1490-1495 (Venice)

'The Claret of the Redeemer', 1496 (Udine)

• Tintoretto (Real name: Jacopo Comin [a.one thousand.a. Jacopo Robusti]) (1518 -1594)

'The Erection of the Cross of the Repentant Thief ', 1565 (Venice)

• Lorenzo Lotto (c.1480-1556) 'Giovanni Agostino della Torre and his son' 1515 (London)

• Moretto da Brescia (c.1498-1554) 'Portrait of a human' 1526 (London)

Recently, a second Last Supper likely executed in Leonardo'south studio during his second Milanese period is on sheet. According to Prof. Jean-Pierre Isbouts, Leonardo himself contributed to some parts and generally assisted in its production.

Leonardo the Experimenter

One cannot forget that Leonardo was not merely a bang-up inventor and innovator, but he was continually experimenting with new ideas and technology. It is timely to note that a small work of fine art executed on vellum in the early 1490s has recently been authenticated as a Leonardo. This is peculiarly noteworthy every bit Leonardo had non been known until now to have produced any finished work on that material, before or since. In his book La Bella Principessa, Martin Kemp writes "Information technology shows him utilizing a medium that has not previously been observed in his 'oeuvre', but one that relates closely to his interest in the French artist Jean Perreal. It testifies to his spectacular exploration and development of novel media, tackling each commission as a fresh technical and aesthetic challenge."

There is every reason to believe, given Leonardo's inquisitive nature and the historical context that he would certainly accept experimented with canvass at the turn of the 16th Century. The pall studies are also specially relevant, as they emphasise Leonardo's classical concerns for accuracy in rendering the folds of wearable, and how they can reveal the human being anatomy beneath.

Leonardo wrote virtually how to pigment on Canvas

Though the foregoing suggests that it would be no surprise that Leonardo used a sail back up for some of his works, one fact pretty well confirms beyond reasonable doubtfulness that he did. In his Treatise On Painting Leonardo describes in particular not merely how to ready canvass for painting, but also how to paint on it in the chapter: Modo Di Colorir In Tela (How to pigment on canvass) – CAP CCCLIII.

Leonardo sets downwardly the basic instructions: "Stretch the canvass onto a chassis, then apply a light glaze of fluid gum and let it dry. So draw your painting with tone using silk brushes calculation, in your mode the "sfumato" technique to identify the shadows while the paint is however fresh. The complexion is made-up of white of ceruse lacquer, and Flanders yellowish; the shadow will be fabricated from black, burnt umber and a little lacquer, or if yous adopt, a hard pencil. Later completing the "sfumato" let the work dry out; and then do dry retouches with a solution of diluted lacquer in gum arabic that has been left a long time. The longer the mixture is left the ameliorate the result, as it remains matt. If yous want your shadows darker, accept the aforementioned gummed lacquer, adding ink. Y'all can use this mixture to shade numerous other colours including azurite, lacquer, etc., considering it is transparent. I have stated for the shadows, now for the highlights you tin make tints from using a simple gum arabic lacquer over the summit of undiluted lacquer and over this is applied a diluted veil of dry out cinnabar."

At present this description is key for two reasons. Kickoff, it demonstrates unquestionably that Leonardo did paint on canvas. All of this noesis was gathered through real life experiences and experiments and information technology would be simply impossible to believe he would describe the details of a process he never executed himself. Second, the level of detail in which he describes the procedure is strongly suggestive that his use of canvas extended beyond simple studies. This implies that at that place would be major works by Leonardo, such as the 'Before Mona Lisa', that were executed on the material. It is believed that about half of Leonardo'due south paintings may notwithstanding be missing or even so to be correctly attributed. Given the above, it is quite probable that a number of these works were executed on canvas support.

Another extremely of import point relating to the 'Before Mona Lisa' is that its very beingness on canvas instead of a forest panel belies any suggestion, and is just one more piece of evidence against the idea, that information technology could ever have been a 'copy' of the Louvre version, or vice versa. Clearly, and equally is discussed in detail in the section about comparisons, Leonardo would have intended to brand two different versions. Furthermore, if Leonardo was considering an opportunity for his before version to be in any way experimental, especially in content or limerick, then it is most credible that he might have used sail every bit a familiar and convenient material.

See in a higher place paradigm of canvas detail, taken from this border of the painting.

The Lining

It is common with very quondam paintings on canvas to reinforce the original back up by attaching it to a new 2d sheet or lining. This process not only strengthens the original support, simply assists greatly in the overall preservation of the pic. In the instance of the 'Earlier Mona Lisa' this attachment was executed by means of a glue mixture: a combination of flour paste, mucilage and Venetian turpentine equally plasticizer. In sure lights, this produces a slightly uneven surface – a difficulty after overcome by the subsequent procedure of hot table-wax lining.

A technical examination of the painting shows that the original canvas was very slightly trimmed when information technology was attached to the lining, but the raw edges of the original paint have not been touched. The new lining is a manufactured fabric of uniform manifestly tabby weave, with an average count of xiv threads per cm for the warp, and 14 threads per cm for the weft. This is the sheet now visible on the back of the work. It was attached to the stretcher with nails. As in that location are no holes from prior nails in the lining, ane can surmise that the present stretcher was put into use when the painting was lined. The pattern of the canvas appears slightly wavy forth some edges, due to irregular degrees of tautness when it was attached to the original stretcher.

The Stretcher

This is the wooden frame upon which the canvas has been made taut. The 1 seen at the dorsum of the 'Earlier Mona Lisa' today is a replacement for the original stretcher. The corners of the lining canvas have been cut back to correspond with the original sheet, the edges glued then trimmed on the stretcher. This probable would non have been the case if this was the original wooden framing stretcher.

The lining is now fixed according to the actual dimensions of the painting, and the wooden wedges inserted at the four corners requite the canvas maximum tension.

The Basis

The base ground layer is composed of a combination of reddish-chocolate-brown ochre and calcite, with some grains of quartz. This colour equally a base of operations, allows to bring out a sense of warmth across the whole painting, where the colours are predominantly earth-tones on the mitt-woven canvas. Significant in the painting's inherent beauty is the conspicuous lack of any potent polychromatic colour: all the elements are in organic harmony, and aid to accentuate the gorgeous skin tones. Part of the reason for this is the reddish-brownish undercoating.

There is also evidence for this approach in other famous Leonardo portraits. Over the space of two years, from 1952 to 1954, his 'Lady with the Ermine', underwent scientific and technical exam at the National Museum in Warsaw. There it was revealed that the background of the painting consisted of a combination of ivory blackness, globe of burnt umber and natural sienna. Another probe, on the subject'southward dress, revealed that the pigment had to be of a ferruginous origin.

''La Belle ', also underwent laboratory testing at the Louvre in the early 1950s. Professor Pietro Marani, in his 2003 volume, Leonardo da Vinci – The Complete Paintings refers to Sylvie Béguin, the distinguished Conservateur-en-chef there, who noted: "The laboratory exams reveal a pictorial surface which is thin and a preparatory ground of cherry earth very close to Leonardo'south technique."

Professor Marani describes the Louvre 'Mona Lisa' as follows: "… Exam under a microscope reveals at to the lowest degree two colours in that preparatory ground: blue under the upper, landscape part; cerise under the lower role. Leonardo used the same two-toned footing in 'La Belle Ferronnière', 'The Musician', and 'St. Anne'."

In improver, a recent written report in the National Gallery Bulletin states that the Prado 'Mona Lisa', which is believed to take been executed by one of Leonardo's administration, also displays a coloured reddish ground.

The American conservation scientist H. Travers Newton, was, in 1974, making a technical inquiry under Vasari'southward frescos in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence to try and locate whatever remnants of Leonardo'due south 'Battle of Anghiari'. The procedure employed was Thermavision – an infra-cerise Vidicon system, super-cooled with liquid nitrogen – in club to probe the walls. This equipment produces a thermal map of materials present beneath the surface: different materials absorb and emit estrus at unlike rates. According to Charles Nicholl: "All the core samples showed a layer of red pigment below Vasari'due south 'intonaco', and some showed other pigments laid over this cherry-red ground. These included 2 suggestive of Leonardo's practice – a green copper carbonate like to that used in the 'Last Supper', for which Leonardo gives a recipe in the Trattato; and blueish smalt, equally institute in the Louvre 'Virgin of the Rocks' … Azurite was also institute, which is non suitable for use in true fresco, and then it suggests the anomalous surface area is non a conventional fresco."

This comment highlights at to the lowest degree 2 split issues. Firstly, regarding Leonardo's fresco work, and some of the reasons his ii major fresco commissions concluded badly: a rash enthusiasm for experimentation with both oils (in the 'Last Supper') and encaustic materials ('The Battle of Anghiari') while eschewing the traditional tempera methods.

Secondly, the prevalent use of a red ground for the Anghiari fresco would have occurred at exactly the same period as the application of reddish footing on the 'Earlier Mona Lisa'. The ii commissions would have coincided, and then it is logical that his palette would take been similar at the time. Traces of smalt and azurite, similar to the findings of Travers Newton, are found in the groundwork mural of the 'Before Mona Lisa'.

In 1998, at the Dublin Congress of the International Found for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, Jill Dunkerton and Marika Spring of the National Gallery, London, presented further relevant information: "With reference to tinted and coloured preparations, from light to mid-tone, the thin pigmented layers found immediately above the gesso may in fact exist monochrome undermodellings of the type seen on unfinished pictures by artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Fra' Bartolommeo, rather than primings … Nevertheless the number of works with tinted and moderately coloured primings … is considerable and includes as many panels as canvasses."

This priming technique was also proficient by numerous contemporaries of Leonardo, including Antonio Allegri da Correggio, Dosso Dossi, Alessandro Bonvicino (Moretto da Brescia), and his student Giovanni Battista Moroni. These painters were popular and prolific in their fourth dimension, and seriously underrated by Vasari. The impression of an artist experimenting with a variety of preparation is supported past the discovery that Correggio'due south large canvasses, 'Venus with Cupid and Mercury', and his 'Danae' in the Borghese Collection in Rome, take a thick carmine-brown priming based on red globe. Stylistically, the overt sensuality of Correggio's paintings contrasts with Leonardo the Florentine's subtle implications. Dunkerton and Jump have also pointed to the relevance which dark preparations offering for a more than rapid and directly execution of the painting. Furthermore, the gray prime glaze found in so many Italian paintings of that period corresponds to all the sample probes taken from the 'Earlier Mona Lisa'.

It can therefore be clearly established that the reddish-brown ground on the 'Before Mona Lisa' is compatible with some of Leonardo's other significant paintings. This ground color could be seen as a signature of the primary's creativity and knowledge of pigments in overcoming challenges to present the colours of the final layers as they should be correctly seen by the naked middle. Leonardo'south all-encompassing use of ruddy-dark-brown ground can also exist noted in his drawings and studies, some of which are in the Purple Library at Windsor, and in the Uffizi in Florence.

The adjacent layer, which is grey with a slight purplish hue, consists of calcite, lead white and os black. Once more, the colours specified above, by Leonardo in his Treatise, are in full use on this portrait. Charles Eastlake states: " … there is scarcely a picture of Leonardo, whatever stage of completion information technology may take reached, which does non exhibit this more or less solid purplish preparation, varying from an ink colour scarcely removed from gray." Eastlake also discusses the treatment of application of the pigments. In relation to Leonardo's technique he writes: "This thinner employ of the opaque colours was still more than requisite in the half-lights, the varieties of which chiaroscuro had already been expressed in the gray or imperial preparation with the utmost nicety: on these therefore, the scumbling colours, disposed to harmonize the subdued lights with the residuum of the piece of work, were spread with a sparing paw, softening withal more the finer markings rounding the forms past almost imperceptible graduations, or equally Lomazzo expresses: With tinted film upon moving picture … Sfumato!"

Larry Keith and Ashok Roy in their message Giampietrino, Boltraffio, and the Influence of Leonardo, 1996, write: "In Leonardo's paintings an overall pictorial unity produced past a tightly controlled, restricted range of tone and value was a fundamental feature. The sculpture-rivalling relief of the National Gallery's drawing of the 'Virgin and Child with St. Anne' and 'St. John the Baptist' (NG 6337), with its severely restricted palette, illustrates Leonardo'due south primary concern with the creation of depth through the manipulation of value, not colour. In painting, while he did develop the techniques of exploiting colour of diminishing intensity to create aeriform perspective, the intrinsic beauty of sure naturally high-fundamental pigments was as a rule deliberately and consistently subordinated to the constraints of his greater tonal subject field.

Near striking is Boltraffio's employ of a dark underpainting ('The Virgin and Kid') of some solidity for much of the limerick, and this seems to have been a primal part of Leonardo's method, and tin exist seen in a number of unfinished works (e.g. 'The Penitent of St. Jerome' and the 'Adoration of the Magi') [Note: Boltraffio was an early student of Leonardo and worked in his studio around the 1490s.] Leonardo used oft a dark mixing oil in all the layers including a dark undermodelling."

A recent study by Menu published in Leonardo Da Vinci's Technical Exercise, the paint pigments of 'La Belle Ferronnière' were detailed equally comprising cerusite, minium, quartz and calcite, quite similar to the 'Earlier Mona Lisa'.

Paint Pigments

In his Treatise On Painting, in the chapter How to Paint on Canvass – CAP CCCLIII, Leonardo sets down the basic instructions, and some of the pigment described tin can exist constitute in the 'Earlier Mona Lisa': "Stretch the canvas onto a chassis, then utilise a light coat of fluid gum and permit information technology dry. Then draw your painting with tone using silk brushes calculation, in your style the "sfumato" technique to place the shadows while the paint is still fresh. The complexion is made-upward of white of ceruse, lacquer, and Flanders yellow; the shadow will exist made from black, burnt umber and a little lacquer, or if you lot prefer, a difficult pencil. Subsequently completing the "sfumato" let the work dry; and so do dry retouches with a solution of diluted lacquer in gum arabic that has been left a long fourth dimension. The longer the mixture is left the better the effect, every bit it remains matt. If you want your shadows darker, take the same gummed lacquer, adding ink. Yous can use this mixture to shade numerous other colours including azurite, lacquer, etc., considering it is transparent. I take stated for the shadows, now for the highlights you tin can brand tints from using a simple gum arabic lacquer over the top of undiluted lacquer and over this is applied a diluted veil of dry out cinnabar."

Occasionally artists would paint directly onto these gesso grounds: in many instances the footing was modified by the application of layers intended to reduce its absorbency. Such a blanket over the gesso is called in Italian an imprimitura, often referred to in English language when writing on Italian painting techniques.

The author Stuart Fleming refers to this base of operations gesso as a ground, instead of it being called the initial preparation of the canvass. The footing coats are really layers of pigments laid downwards over the gesso, to assist in building-up the subsequent layers of paint colours, both opaque and transparent, to create the desired effect.

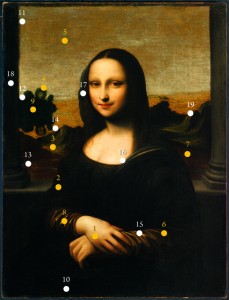

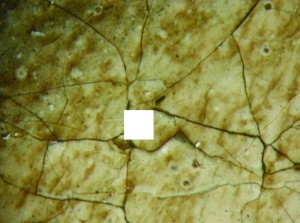

Two series of belittling probes were effected on the painting primarily in order to identify the complete range of pigments and other media used, equally well as to help define some of the techniques he employed in the preparation of the canvas support, and the application of the base, ground and pigment layers. The results not only identified the pigments and other fabric, but too pointed to the sequence in which sections of the work were undertaken. Dr. Hermann Kuhn's nine probes were taken in June 1977, and it was in June 2005, exactly 28 years later, when Dr. Maurizio Seracini dated the results of his further 10 probes. The results are listed chronologically. It is best-selling that there could have been some procedural advances during those 28 years, and the intention here is to exist as comprehensive as possible and to standardise the presentation of the results, where useful..

Except for his starting time probe, which goes to the lowest base layer, Dr. Kuhn's study primarily specifies the surface pigmentation in each case. Dr. Seracini's probes identify the paint material in every layer of each probe. Naturally, there cannot be any direct comparison between the results, as each probe was taken from a dissimilar part of the painting.

Location of the 19 samples taken for pigment analyses.

First analysis: Dr. Hermann Kuhn

Probe #one: Flesh pigment

The lowest layer is a red to red-brown base that is equanimous of crimson-brownish ochre and calcite, and includes a few bigger grains of quartz. There is a subsequent grey layer of base of operations consisting of calcite, lead white and os black. This is covered past the flesh layers which incorporate lead white, calcite, a few grains of blackness vermilion, zinnober* (HgS – Mercury sulphide), vermilion, and yellowish ochre.

[*Editor's note: this is what Leonardo refers to as dry cinnabar]

Probe #2: Apparel, dark-brown paint

On assay it was found to comprise brown iron oxide of manganese umber, vegetable black, pb white, calcite, and ruby-red lacquer.

Probe #3: Mount, yellowish highlight pigment

Two tests were made on the yellowish to greenbrown layer that contained the total of pigments present. It contained vegetable blackness (pulverisation of charcoal), smalt, blue copper pigment obviously fabricated artificially with copper blue – called veriter, azurite in niggling traces, transparent yellow, brown and red grains of iron oxide (burnt green, earth or earth sienna), yellow lacquer, calcite, lead white, and a large quantity of uncoloured glaze.

Probe #4: Tree, green pigment

Big grains of blue pigment in a yellowish brown binding. The assay shows azurite in big quantities, smalt, and grains of pb white. The impression of green is given past an unidentified xanthous (vegetable pigment). On reanalysis of this unidentifiable yellow it was institute that at that place are not whatsoever xanthous pigments except the presence of impurities of iron oxide.

Probe #v: Heaven, pigment

Two pigment samples were taken from different areas of the heaven. Nether magnification it is revealed that the two samples contained calcite, lead white, and a large amount of smalt, which has a fine grain and a very pale colour. A large function of the pigment looks colourless.

Probe #6: Dress, lite brown pigment

The following components were found: brown iron oxide of manganese-umber, xanthous ochre, pb white, little traces of carmine lacquer, and bone black.

Probe #7: Left background, red-brown pigment

It contains a mixture of xanthous and red iron oxide (ochre and world sienna), vegetable black, smalt, calcite, lead white, green earth, and artificial copper blue chosen veriter.

Probe #8: Dress fold, yellow highlight pigment

Contained pb white, calcite, yellow lacquer, yellow fe oxide (ochre), and vegetable blackness.

Probe #ix: Left tree, dark green pigment

Over a greyness-blue layer is a layer containing big grains of smalt and azurite, plus fiddling traces of lead white, and calcite. The very dark tone is caused by an overlaying brownish layer – (vegetable paint), originally xanthous-aged and/or yellowed varnish.

Second analysis: Dr. Mauricio Seracini

Probe #10: Wearing apparel

Layer 1: Cerise ground of earth pigments, natural ochres, lead white, minium, bone black, carbon black, smalt.

Layer 2: Grey layer priming of atomic number 82 white, calcite, carbon blackness, and granules of red ochres.

Layer three: Layer of carbon blackness, lead white, and umber.

Layer four: Dark grayness layer of carbon blackness, umber, and atomic number 82 white.

Layer 5: Sparse grayness layer of calcite, and carbon black.

Layer vi: Dark layer of calcite in a rich bounden medium.

Layer 7: Carbon black, calcite, and lead white.

Layer 8: Varnish

Layer 9: Glaze of carbon black.

Layer 10: Layer of varnish.

Layer eleven: Layer of depression-fluorescent varnish.

Probe #11: Edge of pillar

Layer 1: Cherry ground matrix of earth pigments, incl. lead white, minium, particles of carbon black, and os black.

Layer 2: Gray priming layer of pb white, calcite, and carbon black.

Layer 3: Pb white and partly-decoloured smalt.

Probe #12: Tree

Layer one: Red ground of world pigments, lead white, minium, particles of smalt.

Layer 2: Grey priming coat of lead white, calcite, carbon black, granules of scarlet ochre.

Layer three: Lead white and decoloured smalt-blue.

Layer 4: Azurite and pb white.

Layer 5: Varnish.

Probe #13: Mountain

Layer i: Crimson ground of earth pigments, lead white, minium, particles of carbon blackness, and os black.

Layer 2: Grey priming coat of pb white, calcite, and carbon black.

Layer 3: Thin brown layer of pb white, calcite, and carbon black.

Layer four: Green-blue pigments, plus brown-green layer of lead white, earth pigments, and umber.

Layer five: Double layer of varnish.

Probe #xiv: Edge of tree

Layer 1: Ruddy ground of earth pigments, pb white, minium, particles of carbon black, and bone blackness.

Layer two: Grey priming coat of lead white, calcite, and carbon blackness.

Layer 3: Brown layer consisting of atomic number 82 white, carbon black, calcite, earth pigments, and traces of smalt.

Layer 4: Every bit 'layer 3' higher up, plus azurite.

Layer 5: Decoloured smalt, lead white, and earth pigments.

Layer half dozen: Green/yellow layer of earth pigments, yellow lake, plus green/blue pigment.

Layers 7-9: Iii layers of varnish.

Probe #15: Sleeve

Layer 1: Red footing of earth pigments, pb white, minium, particles of carbon black, and os black.

Layer ii: Greyness priming coat of lead white, calcite, and carbon black.

Layer iii: Light brown layer consisting of lead white, calcite, earth pigments, particles of umber, and yellow lake.

Layer four: Beige layer of atomic number 82 white, calcite, and earth pigments.

Layer v+: Several layers of varnish.

Probe #16: Breast

Layer 1: Blood-red footing of earth pigments, lead white, minium, particles of carbon black, and bone black.

Layer 2: Grey priming coat of lead white, calcite, and carbon black.

Layers 3 and 4: Ii layers of white, consisting of lead white, vermillion, and a few granules of carbon black.

Layer 5+: Several layers of varnish.

Probe #17: Pilus

Layer 1: Red ground of globe pigments, pb white, minium, particles of carbon black, and bone black.

Layer 2: Gray priming coat of atomic number 82 white, calcite, and carbon black.

Layers 3 and iv: Ii layers low-cal brown, of lead white, earth pigments, umber, and bone black.

Layer 5: Particles of decoloured red lake.

Layer 6: Several layers of varnish.

Probe #18: Colonnade

Layer ane: Red basis of globe pigments, lead white, minium, particles of carbon black, and bone black.

Layer ii: Grey priming coat of lead white, calcite, and carbon black.

Layer 3: Brownish layer of lead white, calcite, and globe pigments.

Layer iv: Black layer of lead white, carbon black, and world pigments.

Layer 5: Paint layer – colour unspecified.

Layer half dozen: Dark-brown layer of calcite.

Layer 7: Blackness layer of carbon black, small quantities of lead white, calcite, and earth pigments.

Layer 8: Thin layer of brown organic material.

Layer 9 +: Several layers of varnish.

Probe #nineteen: Mural

Layer i: Ruddy footing of earth pigments, pb white, minium, particles of carbon black, and bone black.

Layer 2: Grayness priming coat of atomic number 82 white, calcite, and carbon blackness.

Layer three: Dark-brown layer of decoloured smalt, lead white, and earth pigments.

Layer 4: Green layer of lead white, world pigments, green/blue pigment, and granules of smalt.

Layer five: Organic brownish coat.

Layer 6: Thin layer of lead white, and world pigments.

Layer vii +: Several layers of varnish.

Both Kuhn and Seracini confirmed that the face and all flesh pigments are like throughout the painting.

The results of the foregoing analyses bespeak that all the pigments that were institute were already available at the commencement of the 16th Century.

It must be noted that in calorie-free of the invasive nature of extracting probes, it was brash and decided non to extract materials directly from the subject's face up. This decision was taken equally it was confirmed that a probe taken from the face would most likely yield identical to those taken on other parts of the subject'south flesh (i.due east. probes #1 and #xvi.

Leonardo's 'Mona Lisa' Palette

A comparison of the pigments used in the 2 Mona Lisas brings interesting results. Lead white, for example is an important elective of both. Regarding the 'Earlier Mona Lisa', both Dr. Kuhn and Dr. Seracini found lead white in every single probe, including the greyness second ground coat. The Louvre report on their 'Mona Lisa' states just that atomic number 82 is present everywhere in the course of lead white.

Other pigments that are common to both paintings include azurite, blue copper, vermilion, umber and even smalt. In fact both pictures feature pregnant amounts of earth pigments such as the diverse ranges of siennas, ochres and umbers; natural enough for a time earlier the development of artificial pigments. There are variations as to how blackness pigments are referred.

Burnt umber, an earth-tone used in both paintings, has wonderful mineral properties: "One may therefore suppose that natural burnt-umber, or an earth pigment rich in manganese oxide, plays an important part in achieving Leonardo's famous sfumato effect. The relative absenteeism of cracks in the shadows of the face can exist related to the drying properties of this paint, which no dubiety originated from Umbria, a region that is also famous for the quality of its earthenware."

Traces of smalt were found exclusively in the groundwork landscape of the 'Earlier Mona Lisa'. Its popularity in creative person'south pigments actually just took-off in the 2nd half of the 16th Century; however according to senior scientists at the Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musees de French republic (C2RMF) the utilize of smalt in easel painting was well known, though to a more than limited extent in the second one-half of the 15th Century. Pascal Cotte of Lumiere Applied science in Paris, who has examined the Louvre's 'Joconde', 'Lady with the Ermine', and the 'Earlier Mona Lisa' concurs and states that smalt was well in employ at the beginning of the 16th Century, and it is noted by the Louvre in the analysis of its Mona Lisa to be abundantly nowadays.

A trouble that many artists of that time had to face was the lack of ready availability of the pigments they required. Grinding minerals and earth-pigments with the correct media, to the right consistency and shade was a laborious and therefore expensive process. Many of these pigments " … being imports every bit far as colour-merchants in the chief fine art centres of Italy, the Netherlands, French republic and England were concerned, were expensive and non e'er so readily bachelor. Consequently, we can imagine that artists were eager to learn of any human-fabricated pigments that could serve as alternatives to the traditional palette."

In the same extract from Leonardo'due south Treatise higher up, at that place is a reference to " … a diluted veil of dry cinnabar … " This exists on the 'Earlier Mona Lisa', noted as 'zinnober', in a probe of one of the mankind tones, just is not mentioned for the Louvre 'Mona Lisa'. That painting shows a modest amount of vermilion in some of the mankind tints, as does the 'Before Mona Lisa'. Leonardo cited red lac, or lake as the correct pigment for shadows and calorie-free areas. Over again, both paintings show traces: on the face of the younger adult female, and on the hands of the Louvre 'Mona Lisa'.

In other chapters of his Treatise, Leonardo frequently refers to the employ of lake, or red lake, especially for flesh tones: "L'incarnatione fara biacca, lacca, e giallolino: l'ombra fara nero, e majorica, east united nations poco di lacca, o vuoi lapis duro." ("The flesh color may be made with white, lake, and Naples yellow. The shades with blackness umber, and a little lake; y'all may, if you delight, employ black chalk.").

The authors of the slap-up volume, Mona Lisa – Inside the Painting have admitted in the book that quotations and analyses from Leonardo'due south Treatise concern painting on sail. In a way, this is an oblique though fair acknowledgement that Leonardo would have had substantial experience with that textile, and confirms that not only did he utilise canvas extensively, but executed significant works on it. To be even-handed, it is also reasonable to presume that, given the right preparations, whatever of his formulas for painting on canvas could be configured, perhaps in different combinations, to exist every bit effective on wood.

The comment in the publication likewise highlights an issue that until now has rarely been tackled: a comprehensive study of Leonardo's work on canvas. Elisabeth Martin, Naoko Sonoda, and Alain Duval comment: "All the major studies and articles on the preparation and pigment compounds of paintings of the Renaissance period in Italy, and specially around Leonardo's years, chronicle to paintings on wood simply, and till recently little or nothing was studied on Leonardo'southward works on canvas or other surfaces." Certainly later the intense examinations undertaken on the 'Earlier Mona Lisa', ane could gain a new understanding of Leonardo'due south working techniques.

Interestingly with this painting, at that place are really no surprises: it fits with Leonardo'southward own detailed and comprehensive directions, as he outlined both in the voluminous writings and reports assembled throughout his life, but likewise specifically in his Treatise On Painting, required reading for whatsoever true artist and student of Renaissance painting. No other artist of his fourth dimension left such a wealth of information, either about his particular vocation, or useful instructions on how to achieve elevation results.

Dating

A) 210Pb measurement by gamma spectroscopy on a Atomic number 82 White sample

This test is valuable in identifying the nature of pb-white, which can indicate if the artwork was executed more than 250 years ago. If the carbon content is completely rust-covered, the work was executed more than 250 years ago. To detect the presence of 210Pb radioisotope, the Lead White sample 7 was analysed with a Gamma Spectrometer for 278 hours, with a high resolution and low noise detector GX-HP Ge (ORTEC).

i – Carmine ground layer of earth pigments. Pb White, Minimum, and some particles of Carbon Black. ii – Gray layer of Lead White, Calcite, and Carbon Blackness. iii – White layer of Lead White, Cinnabar and Carbon Black. four – Layer of varnish.

A Radioisotope is considered totally decayed when 12 t1/two are passed. The information show that all 210Pb isotopes nowadays in the sample analysed were completely decayed. Since 210Pb has a t1/2-20.4 years, materials in the sample examined are certainly more than 250 years old, a dating which may go back to the early 16th Century. The materials with Pb in sample 7 are three: in the priming [2PbCO3 – Pb(OH)2]; in the minium [Pb304]; in the upper gray layer and in the white layer, of pb white, cinnabar and carbon black.

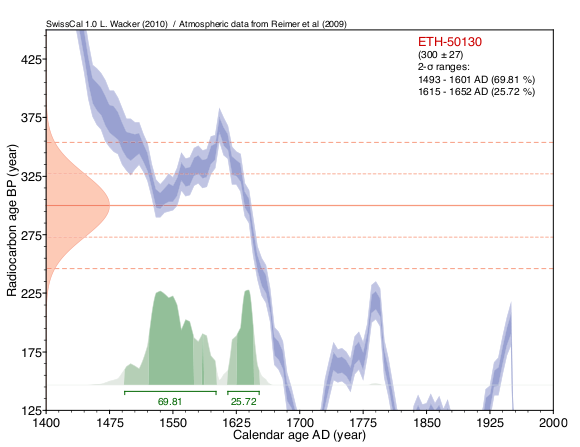

B) Carbon Dating

'Carbon Dating' (or 'Radio Carbon Dating') procedures can exist a valuable tool in the fine art world for the complicated purpose of dating paintings. This is a radiometric dating method using naturally occurring radioisotope carbon -xiv (14c) to determine the age of carbonaceous and other organic material, every bit far back every bit about 60,000 years. Though carbon dating is not conclusive as a test taken by itself, it can confirm a spread of years earlier which a painting could not have been executed.

In full general, carbon dating tests provide a window of years, which can be quite large. Other than the probability percentages of certain years within the window, there is no way to know the likelihood of each yr. A contempo example which demonstrates this exercise was undertaken amid other tests on the vellum support for 'La Bella Principessa', a work afterward authenticated past Martin Kemp and others, equally being an autograph work by da Vinci. The result of that test gave " … a 95.4% probability of a bracketed date of Ad 1440 – 1650 …" Obviously this 210-year spread cannot institute a Leonardo attribution. However, the exam does date the vellum support itself, just not the actual artwork on it.

Carbon Dating results obtained past ETH, Zurich

As previously described, the original handmade sail of the 'Earlier Mona Lisa' has been relined on a much afterwards motorcar-made sail. The original painting and canvas cover the entire facing surface, simply hardly any of the original canvas folds effectually the sides of the existing stretcher. However, a very small but acceptable sample of the original sail was sacrificed and extracted for radio carbon dating from a zone located on one edge.

This test yielded a dating of the canvas between 1492 and 1652 (run across graph), with a higher probability in the earlier part of that period. This date range is a standard and is one that is typically expected for dating results of paintings executed in the early 1500s. This exam confirms that the sheet used in the 'Earlier Mona Lisa' can indeed be from the menstruation during which Leonardo would have painted it, and fits with the chronology documented past Giorgio Vasari and the 1503 date confirmed by Agostino Vespucci.

Professor Hans-Arno Synal, of the Swiss Federal Institute of Applied science, Zurich on reviewing the results of the test, states: "Information technology is therefore clear that materials, which would have been originating at the plow of the 16th Century, would certainly give a similar radiocarbon age every bit the final issue we have at present achieved … "

Source: https://monalisa.org/2012/09/08/leonardos-materials-the-canvas-the-paint/

0 Response to "What Materials Did Leonardo Da Vinci Use to Create His Art?"

Postar um comentário